The ABCs of Partnership

Five strategies that pull Finance off the sidelines and into every decisive huddle

In my interview with Glenn Hopper on the FP&A Today Podcast, we discussed how to transform Finance teams into strategic partners. I hinted at the answer there, but I wanted to take the time to fully develop the playbook.

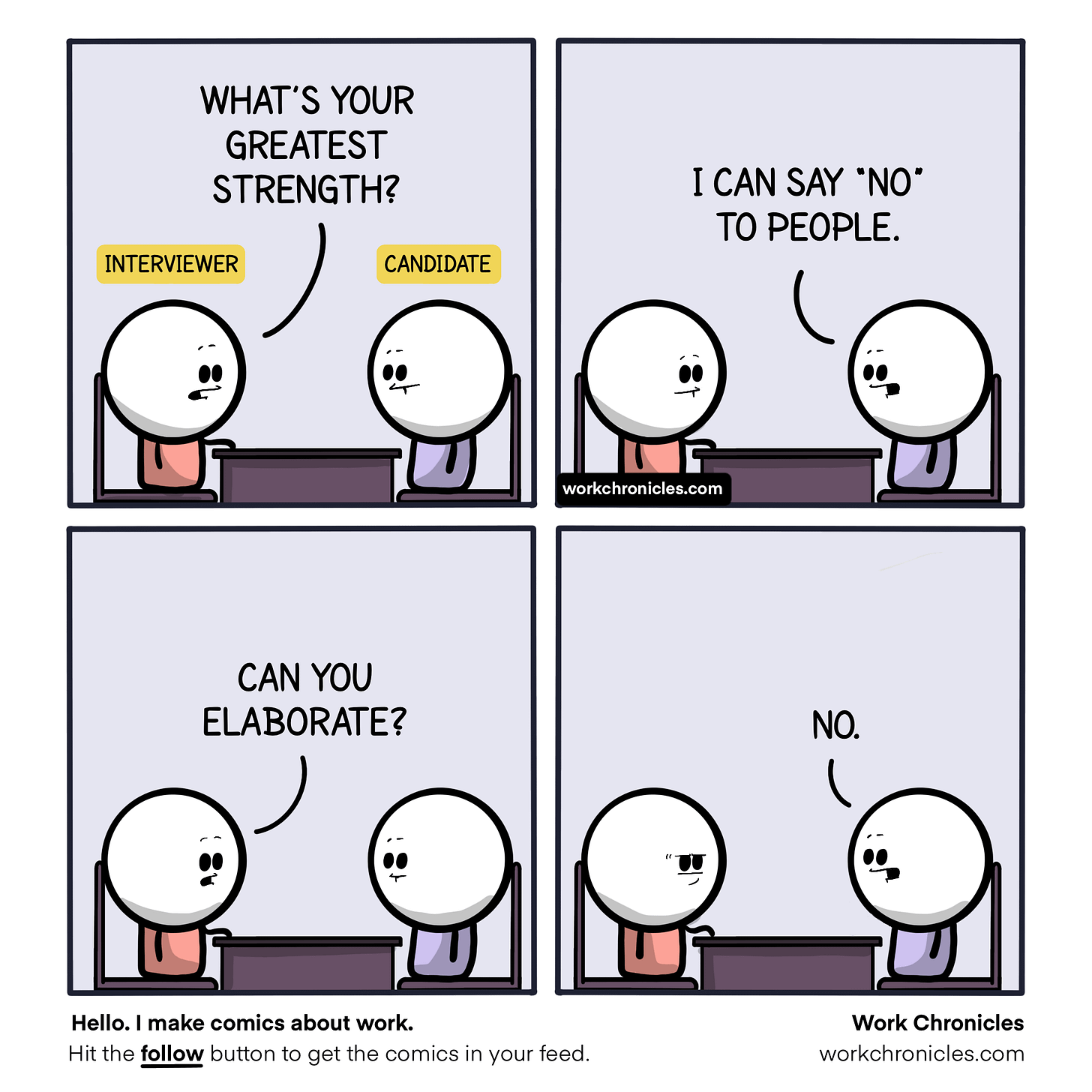

As finance leaders, we face a unique paradox: we have unprecedented visibility into every aspect of the business, yet we're often the last to be invited into strategic conversations. While other departments chase growth and innovation, we're cast as the responsible parent, expected to say "no" and protect the bottom line. Our position gives us the perfect vantage point to drive value, but our reputation as scorekeepers keeps us stuck on the sidelines.

We have to earn our spot on the field through partnership.

But not just any partnership. Finance leaders face unique challenges in building trust: we're expected to be both watchdog and advisor, to maintain control while enabling growth, to say "no" while finding ways to say "yes." Success requires a delicate balance of oversight and enablement that most partnership advice fails to address.

In this article, we'll explore "The ABCs of Partnership," a framework specifically designed for finance leaders who need to maintain control while building trust. These principles will help you transform from gatekeeper to strategic partner without compromising your essential oversight role. Whether you're a CFO looking to increase your strategic impact or a finance manager trying to build better business relationships, these battle-tested approaches will help you navigate the unique tensions finance leaders face in building partnerships.

Aim to Assist

Shift your focus from making an impact to being useful.

As finance professionals, we're trained to focus on controls, compliance, and risk management. These are essential responsibilities, but they can trap us in a reactive stance - waiting to say "no" to bad ideas rather than helping shape good ones. The most effective finance partners flip this dynamic by asking a simple question before every interaction: "How can I be useful here?"

Consider two finance leaders reviewing the same out-of-budget marketing request:

Leader A focuses on policy: "This exceeds your quarterly budget by 20%."

Leader B focuses on being useful: "What outcomes are you targeting? Let me help you build a business case that justifies this investment."

Both leaders maintain financial oversight, but Leader B's approach transforms a potential conflict into an opportunity for partnership. They're not just enforcing rules - they're helping their partner succeed within those rules.

The key is to step back and ask yourself, "Am I being useful?" If that feels unnatural, here are a few other ideas to maintain an aim to assist the business:

Look for friction points. Some friction between finance and business partners is inevitable and even healthy - we need controls and oversight. But unnecessary friction often signals an opportunity to be more useful. For example, if your approval process consistently causes last-minute fire drills, that's a friction point you can solve by getting involved earlier in planning cycles. Or if business partners frequently challenge your allocations, perhaps the methodology needs to be more transparent or better aligned with how the business operates.

Start with "why". When a sales leader requests a higher commission rate, they're not really asking about compensation - they're trying to solve for growth or retention. When product wants to increase their AWS spend, they're thinking about customer experience, not infrastructure costs. By understanding these underlying "whys," finance can shift from reactive approval to proactive problem-solving. Instead of just saying yes or no to the specific request, we can help shape solutions that achieve the business goal while maintaining financial discipline.

Challenge your assumptions. As finance professionals, we're trained to think in binary terms: compliant or non-compliant, over or under budget, approved or rejected. But most business decisions live in the grey area. Instead of defaulting to "no" when a request exceeds budget, ask "what would have to be true for this to make sense?" Maybe it's finding offsetting savings elsewhere, phasing the investment differently, or building in success-based triggers. The goal isn't to abandon financial discipline, but to find creative ways to enable good business decisions within our control framework.

Build Clear Boxes

Collaboration requires trust; trust requires transparency

Finance departments are often seen as the ultimate "black box" - mysterious places where business requests go in and seemingly arbitrary decisions come out. Budget submissions disappear into a void, only to emerge months later as approved or rejected. Allocation methodologies remain opaque until they show up on P&Ls. Planning assumptions stay hidden until they become constraints.

These black boxes create friction not because partners disagree with our decisions, but because they don't understand how we make them. The irony? We're following rigorous processes and clear principles - we just haven't made them visible to others.

Here are a few ways to apply clear-coating:

No grand reveals. Classic storytelling suggests the best way to tell a story is to build up to a conclusion, a grand reveal, that rewards the audience with the coveted "aha!" moment. The reverse is true in Business Partnering. When a Marketing VP asks about their Q2 forecast, their heart stops if you open with "Well, let me walk you through our methodology..." They're wondering if they're about to hear bad news. Instead, start with "You're tracking 5% ahead of plan, and here's why..." Then, if they're interested in the details, you can explain how your forecasting model works. This builds trust by showing you understand their priorities while maintaining the rigor of your analysis.

Make complex models accessible. Your FP&A model might span 20 tabs with complex macros and lookup tables, but your business partners don't need to see that engine room. What they need is a dashboard that shows them what drives their numbers. For example, when Sales asks about commission forecasts, give them a simple input template that mirrors how they think about their business: pipeline stages, close rates, average deal sizes. Behind the scenes, your model can do the heavy lifting, but they see only what's relevant to their decisions.

Turn black box processes into decision trees. Instead of keeping approval criteria mysterious, show partners exactly how decisions get made. If someone wants to hire above budget, don't just say, "It needs CFO approval." Share the decision tree: "If the role generates revenue within 6 months, it goes to the VP. If it's longer or doesn't have a direct revenue impact, it needs the CFO's sign-off. If it's strategic and above $X, it goes to the CEO." This doesn't reduce your control - it just helps partners make better requests.

The key isn't to eliminate every black box - some complexity in finance is necessary and valuable. The goal is to make our processes clear enough that partners trust our decisions even when they don't get the answer they wanted.

Close the Loop

Elevate information to insights by emphasizing the “so what.”

Every month, finance teams produce mountains of reports: P&Ls, variance analyses, KPI dashboards. But here's the painful truth: most of these reports don't drive action. They sit unread in inboxes or get skimmed during meetings without changing decisions.

Why? Because we're answering the wrong question. Our partners don't just need to know if they're over or under budget - they need to know what to do about it. They don't just want to see this month's metrics - they want to understand what those metrics mean for their decisions.

In short, to elevate information to insights, we must emphasize the "so what."

Here are three ways to close this loop between information and action:

Connect metrics to decisions. When Engineering is 20% over their cloud spend budget, don't just report the variance. Connect it to choices: "At this burn rate, we'll need to either reduce development environments by 30% or cut planned feature work to stay within the annual budget. Here are three specific ways to optimize spend without impacting velocity..." This transforms the report from an FYI to a decision framework.

Make trends actionable. Instead of just noting that customer acquisition costs are rising, show what's driving the increase and what it means: "CAC has increased 40% due to lower conversion rates in paid channels. At current trends, we'll exhaust our Q3 marketing budget by August. Here are the specific campaigns driving the increase, and here's how adjusting our channel mix could bring costs back in line while maintaining growth targets."

Focus on futures, not just facts. Monthly business reviews shouldn't just recap what happened - they should shape what happens next. Rather than ending with "Marketing missed their pipeline targets," close the loop: "Marketing's current program mix is generating 30% less pipeline than needed for Q4 targets. Based on our campaign attribution analysis, shifting budget from events to digital could close this gap. Here's the specific reallocation we'd recommend..."

Default to "Yes, And"

Break free from the "Department of No"

Every finance leader knows this moment: A product team excitedly presents their new initiative. The ROI looks promising, the strategy is sound, but... it wasn't in the budget. The old you would have stopped there: "Sorry, no budget." But that response doesn't just kill the idea - it kills future collaboration. Next time, they'll try to work around finance instead of with us.

The irony? Finance teams often say "no" to protect the business, but this reflexive response actually creates more risk. When teams stop bringing ideas to finance early, we lose our chance to shape initiatives before they become problems. We become a roadblock to avoid rather than a partner to engage.

Here's how to change this dynamic without compromising financial discipline:

Replace "No" with "Yes, and..." When the Sales team wants to double their headcount mid-year, don't start with budget constraints. Start with: "Yes, it’s important to avoid being understaffed going into the summer months, and to get approval, we’d need to show a 3-month payback period. What if we phased the hiring to match pipeline growth? Let's model out different scenarios." This keeps the conversation focused on solutions while maintaining financial guardrails.

Turn constraints into catalysts. When Marketing proposes an unbudgeted campaign, don't reject it outright. Instead: "Yes, this could work, and we'd need to find the budget elsewhere. I noticed your events program is under-delivering - could we reallocate from there? That would let us test this new approach without increasing overall spend."

Make trade-offs explicit. When Engineering requests more cloud spend, frame it as a choice: "Yes, we can increase the infrastructure budget, and we'd need to offset it somewhere. Would you rather reduce contractor spend or delay the office expansion? Let's look at the impact of each option." This transforms budget discussions from yes/no decisions into strategic choices.

Eliminate Ambiguity

Unknowns are inevitable; bias to action is a force multiplier.

"We need more data before we can make that decision."

It's finance's reflexive response to uncertainty - asking for more information, more analysis, more proof. But this instinct often masks a deeper truth: we usually have enough data to act. We just don't want to take the risk of being wrong.

The real skill isn't gathering more data - it's making confident decisions with the information we already have. Our job isn't to eliminate every uncertainty through analysis, but to help the business take smart risks with the insights already available.

Here's how to turn develop a bias for action:

Start with what you know, then bound what you don't. When evaluating a new market entry, don't get lost in the unknowns. Start with, known costs. Then build ranges for uncertainties: "Our TAM is $500M. At 2-5% penetration (based on similar launches), that's $10-25M revenue. Even at the low end, with our 40% margin, we'd hit ROI targets." This transforms abstract uncertainties into concrete scenarios.

Put numbers on paper. When debating expansion plans, don't let discussions stay theoretical. Draft a simple model with explicit assumptions: "Here's version 1 - I assumed X% growth, Y% margins, and Z% overhead. What looks wrong?" Having something concrete to critique is more productive than endless speculation. The model will be wrong, but it makes the discussion specific and actionable.

Define the decision threshold. In technology investments, it's tempting to endlessly refine estimates. Instead, name your criteria up front: "We need 25% IRR to proceed. Given what we know about costs and benefits, what would have to be true about adoption rates to hit that threshold?" This focuses analysis on what matters for the decision, not theoretical perfection.

The goal isn't to eliminate every uncertainty - it's to identify which unknowns actually matter for the decision at hand, and to make those unknowns concrete enough to act on.

Conclusion

Every finance leader faces the same fundamental challenge: How do we maintain necessary control while building true partnership? The old model - where finance focuses solely on protecting the business through rigid controls and endless analysis - creates the illusion of safety while actually increasing risk. When partners view us as obstacles, they work around us. When we demand perfect information, we miss opportunities to shape decisions early.

The ABCs offer a different path. Being useful rather than just being right. Making our processes transparent instead of mysterious. Turning reports into action drivers rather than historical records. Finding ways to say "yes, and" instead of defaulting to "no." And most importantly, having the courage to act on the information we have rather than hiding behind requests for more data.

This isn't just about being a better partner - it's about being a more effective guardian of the business. Because true financial leadership isn't about controlling every decision - it's about building the trust and frameworks that help the business make better decisions on its own.

Ready to share this?

If you found it helpful, forward it to your team or peers. Great finance leaders spread clarity, not chaos.

And, if you haven’t already, please subscribe to never miss a post!

And, finally, check out my full interview with Glenn here: