No More Dr. No

How Smart Finance Leaders Say Yes Without Losing Control

Early in my career, I earned the unfortunate nickname “Dr. No.”

Some form of this moniker is pervasive for gatekeeper organizations, bordering on the banal. Finance is no exception.

Chief No Officer. The Office of No. The No It All. Ok…the last one is pretty funny, but you get the gist.

It’s understandable why this stereotype exists. Resources are scarce, the allocation of which creates a natural (arguably healthy!) tension between Operations and Finance. If you think of the business as a car, the two operate as the gas and brake pedals, respectively, with the intention that the tandem creates a smooth ride - not too fast, not too slow.

Perceived through this lens, it is expected - predestined, even - that Finance has to say “no” a lot. Otherwise, the car will continue to speed up, eventually careening off the proverbial fiscal cliff.

In practice, stepping on the gas and breaks in quick succession (if not simultaneously!) is anything but smooth. Ideally, the brakes are only applied in emergencies or transition points. You don't have to rush to slow down if you’re conscious about when to speed up!

As a recovering no-aholic, I discovered that the solution to this problem came from an unexpected place: improvisational theater. By adapting their techniques, I developed a response framework that preserves Finance's role as a partner and financial steward while breaking free from the "Dr. No" stereotype.

The key? Starting with "yes."

Yes, And

In the early days of improvisational theater, performers often tried to one-up each other with clever quips or jokes. This competition undermined the scene, with performers losing confidence in each other and audiences losing interest. Anyone who has watched Michael Scott's painful attempts at improv on The Office has seen this dynamic in action—the constant need to be the star kills the collaborative spirit that makes scenes work.

In the 1950s, a group of performers known as The Second City experimented with a different approach. Rather than competing to be the funniest individuals, they focused on how to be the funniest group. Rejecting each others’ ideas on stage was killing momentum, but simply saying “yes” wasn’t enough to build momentum as the onus to develop the scene reverted to one individual. The best scenes were those that leveraged all of the talents on stage.

This insight led to the development of “Yes, And,” where performers would accept and, most importantly, build on each other’s ideas instead of trying to outdo them. The intent is not to develop every idea but to maximize momentum by focusing energy on building upon each other rather than tearing each other down. Often, the words “yes, and” aren’t even uttered - the new information is implicitly accepted and built upon.

As you watch the scene above, notice how ideas are treated as abundant rather than scarce. Not every concept is expanded upon - many are acknowledged and allowed to fade away - but the duo never stops to debate what’s been added to the scene. This is the real power of Yes, And - the performers leverage each other’s contributions in linguistic judo to move towards an aligned objective.

Now that we understand what Yes, And is, let’s turn our attention to how leveraging it will disqualify you from winning the “No”bel prize.

The V/C Response Framework

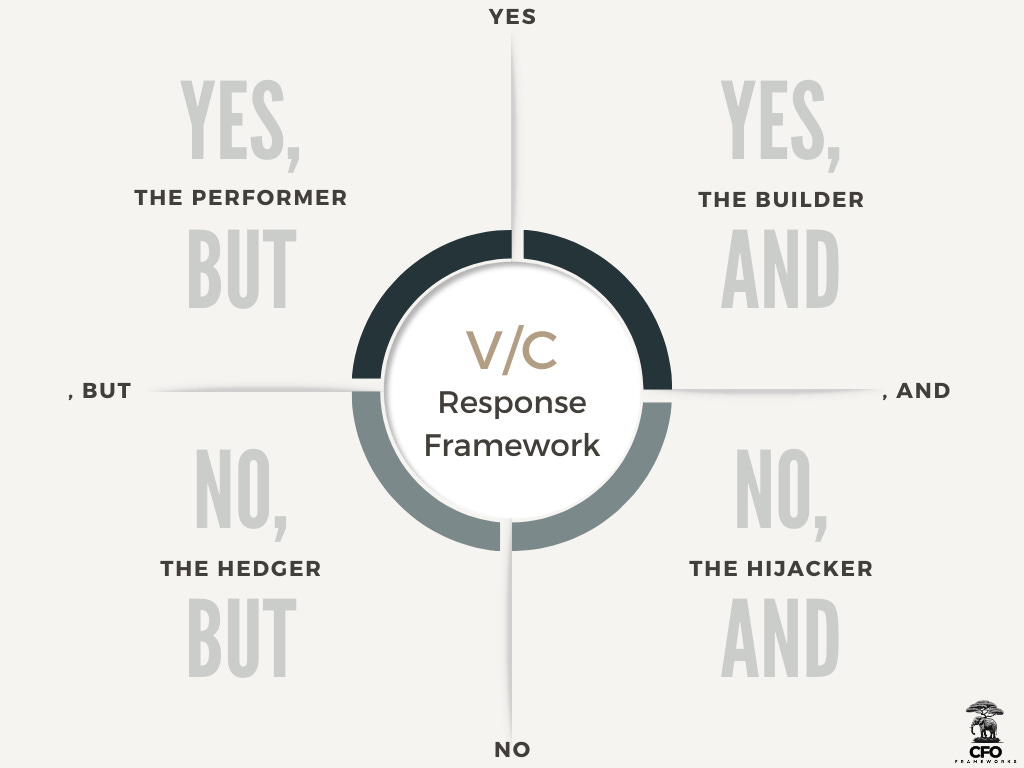

When presented with an idea, we effectively have two decision spectrums to factor into our response: validation (V) and collaboration (C).

Validation (no → neutral → yes) reflects the degree to which someone feels heard, irrespective of the approval outcome.

Collaboration (conflict → neutral → collaborate) reflects the effort to build towards a desired outcome, irrespective of the degree to which the proposed idea factors into that equation.

The key to the point above is that the quality of the response is not based on the decision but on the presentation. How we respond is just as important as what we say. This framework suggests that we can make someone feel heard and valued, even if their suggestion is rejected.

In How to Castrate a Bull, NetApp co-founder Dave Hitz describes how he leverages this framework to defend unpopular decisions.

Let’s say you have decided to pursue Plan A. As a manager, it is part of your job to defend and explain that decision to folks who work for you. So when someone marches into your office to explain that Plan A sucks, and that Plan Z would be much better, what do you do?

My old instinct was to listen to Plan Z, say what I didn’t like about it, and to describe as best as I could why Plan A was better. Of course, the person has already seen these same arguments in the e-mail I sent announcing the decision, but since they didn’t agree, they must not have heard me clearly, so I’d better repeat my argument again, right? I can report that this seldom worked very well.

It works much better if I start out by agreeing: “Yep. Plan Z is a reasonable plan. Not only for the reasons you mentioned, but here are two more advantages. And Plan A—the plan that we chose—not only has the flaws that you mentioned, but here are three more flaws.” The effect of this technique is amazing. It seems completely counterintuitive, but even if you don’t convince people that your plan is better, hearing you explain your plan’s flaws—and their plan’s advantages—makes them much more comfortable.

Yes, And is not about agreeing with someone. It’s a technique to recognize the value of and encourage participation in the ideation process. It’s a belief that we’re at our best when moving forward rather than stopping or looking backward.

The Four Response Types (And Only One That Works)

Picture this: You're in a meeting, and someone pitches an idea. At that moment, you have four ways to respond.

Three will mark you as Dr. No.

One will transform you into a trusted partner.

Let's dissect them:

Looking at the quadrants, it becomes clear why more than half of common responses effectively translate to "no":

"Yes, But..."—The Performer. As Jon Snow wisely notes in Game of Thrones, "Everything before the word 'but' is horseshit." This response masquerades as support while delivering rejection. It's like starting a breakup with "You're amazing, but..." Everyone knows what's coming, and that initial "yes" makes it worse. Try this: Strip out the "yes" and see if your message changes. Spoiler alert: it won't.

"No, But..."—The Hedger This is the corporate equivalent of "I'm not sure I can make it to your party." It's a “no” disguised in maybes and caveats. When we lead with "No, but," we're either unsure of our authority or trying to soften the blow. Either way, we're eroding trust. Better to be clear than wishy-washy.

"No, And..."—The Hijacker This response comes in two equally problematic flavors; both stem from ego and kill collaboration faster than a Game of Thrones wedding.

The Opportunist: "No to your idea, and let me tell you about my completely unrelated agenda!"

The Supreme Leader: "No to your feature X, because my feature Y is clearly superior!"

"Yes, And..."—The Builder. Finally, the response that changes everything. This isn't about rubber-stamping every idea. It's about saying, "I hear you," and "Let's see what's possible." When you respond with "Yes, and," you're not approving the specific request—you're approving the collaboration.

Think of it like improv comedy: The best scenes happen when performers build on each other's ideas rather than competing for the spotlight. "Yes, and" keeps the momentum going while steering toward better solutions.

Remember: The goal isn't to be the person who says yes to everything. It's to be the person who helps find the path to better outcomes.

To help ground the theory, let’s apply it to an everyday use case. Imagine a business partner approached you for approval to throw an unbudgeted, expensive year-end party to celebrate the team’s efforts throughout the year. This matters a lot to the team, and there is no question that the budget cannot absorb this incremental spend. Which response do you believe will be best received?

Yeah…that sounds like a good idea, but we can’t afford it.

We don’t have that in the budget, but you’re welcome to follow up with the CEO to see if he’s willing to take that hit to the P&L.

We can’t afford it (followed by a bah-humbug for good measure).

We don’t have that in the budget, and candidly, I’m not sure we should be throwing a celebration when our gross margins have eroded over the last three quarters.

That sounds like something the team would appreciate, and given how we’re pacing on the P&L, we’ll have to figure out a way to fund it.

Unless you take distinct pleasure in disappointing others, #5’s Yes, And is the winner here. The same message is delivered in all instances (we don’t have the budget), but the response validates the requestor and shifts the discussion to how to do what they want within the current constraint environment. By inviting the requestor into the process, the question is reframed from “can I spend this money” to “what am I willing to give up to have this party.” This is no longer a yes/no question; it’s a trade-off question.

Poof, no more Dr. No.

Why This Matters

The shift from "Dr. No" to "Yes, And" isn't just about making Finance more likable—it fundamentally transforms how organizations make decisions and allocate resources. When Finance leads with "No," three harmful patterns emerge:

Shadow Spending - Teams learn to hide expenses or fragment them into smaller, under-the-radar purchases.

Decision Paralysis - People stop bringing ideas forward, creating a culture of risk aversion.

Us vs. Them - The organization splits into camps: those who "make things happen" and those who "prevent things from happening."

In contrast, when Finance leads with "Yes, And," we see:

Better Ideas - When people help shape a solution rather than defend against objections, they invest more deeply in its success. Instead of working around constraints, they work with them.

Earlier Influence - By being seen as an enabler rather than a barrier, Finance gets a preview of initiatives while they're still forming. This early seat at the table means more opportunity to shape direction, not just approve or deny.

Stronger Partnerships - Teams stop viewing Finance as the department of "no" and start seeing us as collaborative problem-solvers. This trust leads to more transparent discussions about challenges and constraints.

Most importantly, this approach preserves what matters: financial discipline. We're not saying yes to everything—we're creating an environment where constraints breed creativity rather than frustration.

Tips on How to Say Yes, And

While simple in concept, mastering "Yes, And" requires deliberate practice and a shift in mindset. Here are specific techniques to help you break free from the "No It All" reputation:

Seek the Why before the Why Not. When your sales leader proposes hiring three new reps in a hiring freeze, resist the urge to say, "We can't afford it." Instead, understand the underlying need: "We're losing deals because we can't cover our territories." Now you have a foundation to build upon: "I see how coverage gaps hurt revenue. What if we reallocated our most experienced reps to high-value accounts and hired one strategic SDR to support them?"

Lead with Questions, Not Answers. When you're struggling to find the good, get curious: "Help me understand what problem this solves?" or "What would success look like?" Often, the real opportunity isn't in the initial proposal but in the underlying need.

Ban the But. Our brains are wired to forget everything before the word "but." That seemingly harmless conjunction erases any goodwill built by your initial agreement. Eliminate it from your response template, and watch how andnaturally creates bridges instead of walls: "That's an innovative approach, and here's how we could make it work within our budget constraints."

Build the Chain. Each And should invite another. Picture a product launch discussion: "Yes, we could accelerate the timeline, and if we reallocate Q3 marketing spend..." which leads to "Yes, and we could start pre-sales earlier..." which leads to "Yes, and that would give us customer feedback before full launch..." Watch how momentum builds as each person adds their link to the chain.

The Final Yes

Breaking free from being Dr. No isn't just about changing how we speak—it's about transforming how we think about our role in the organization. Finance professionals aren't here to say no; we're here to help find the way to yes. When we lead with curiosity instead of judgment, with collaboration instead of control, we become true partners in building the business.

The next time you feel that reflexive "no" rising to your lips, pause. Seek the why before the why not. Ask questions before giving answers. Ban the but. Build the chain. You might find that the best way to protect the business isn't by being Dr. No—it's by being Dr. Know-How-To-Make-It-Happen.