The Dangers of Playing it Safe

Why Defensible Choices Often Lead to Forgettable Outcomes

Call me a safe bet, I’m betting I’m not

I’m glad that you can forgive

Only hoping as time goes, you can forget

-Brand New, The Boy Who Blocked His Own Shot

One of the great ironies of life is we have a strong tendency to play it safe, even if it costs us the win.

In boardrooms and budget meetings, we make choices that seem prudent and wise: spreading resources evenly to avoid risk, maintaining systems that "still work," and preserving structures that have "always worked."

Each careful choice helps us avoid failure. And each careful choice guarantees we'll never achieve excellence.

The issue stems from a cognitive bias called loss aversion, where the pain of loss is felt twice as intensely as an equivalent gain. This psychological quirk makes us excellent at avoiding downside but terrible at capturing upside.

Imagine finding $20 on the street only to have it blown out of your hands by a strong gust of wind. Economically, you’re in no worse a spot than before you found the money, but you feel worse because it feels like you lost $20 ($20 gain - $40 loss).

When triggered, this predilection for avoiding a loss causes us to conflate safety with success. While the two can lead you to the same choice, they aren’t synonymous.

The safe choice is nestled in averages. As the old saying goes, there’s safety in numbers, so when threatened, we look to conform to what most people would do in our shoes. There’s little, if any, upside to be had because we’re seeking the herd's protection rather than leading the pack.

That’s not to say there isn’t value in using common sense. Sometimes adequate is sufficient. This gets us in trouble when there’s dissonance between what we want and the behaviors we exhibit. When we want to be great but we deliver average.

This psychological dynamic creates a predictable pattern in professional decision-making, one that Howard Marks, co-founder of Oaktree Capital Management, captured perfectly in his memo "Dare to Be Great." His simple framework reveals why the safest path so often leads to mediocrity:

His overarching point is that superior results require a synthesis of unconventionality and accuracy, as payoffs can only be high when a select few are particularly prescient. This is effectively the Pareto principle in action - 20% of the activity will deliver 80% of the results.

What goes unnoticed, though, is how appealing the bottom two quadrants are. Sure, you can’t be elite by following the consensus, but delivering average on a consensus position is defensible. It’s safe. If you aim to maintain the status quo, you’re better off sticking with the like-minded masses rather than venturing outside the box with the non-consensus few.

Finance leaders face this same dynamic daily. Whether it's sticking with legacy systems despite their inefficiencies, maintaining conventional reporting structures that blur accountability, or spreading resources evenly across initiatives rather than betting on breakthrough opportunities - the "safe" choice often feels easier to defend than the bold one that could deliver extraordinary results.

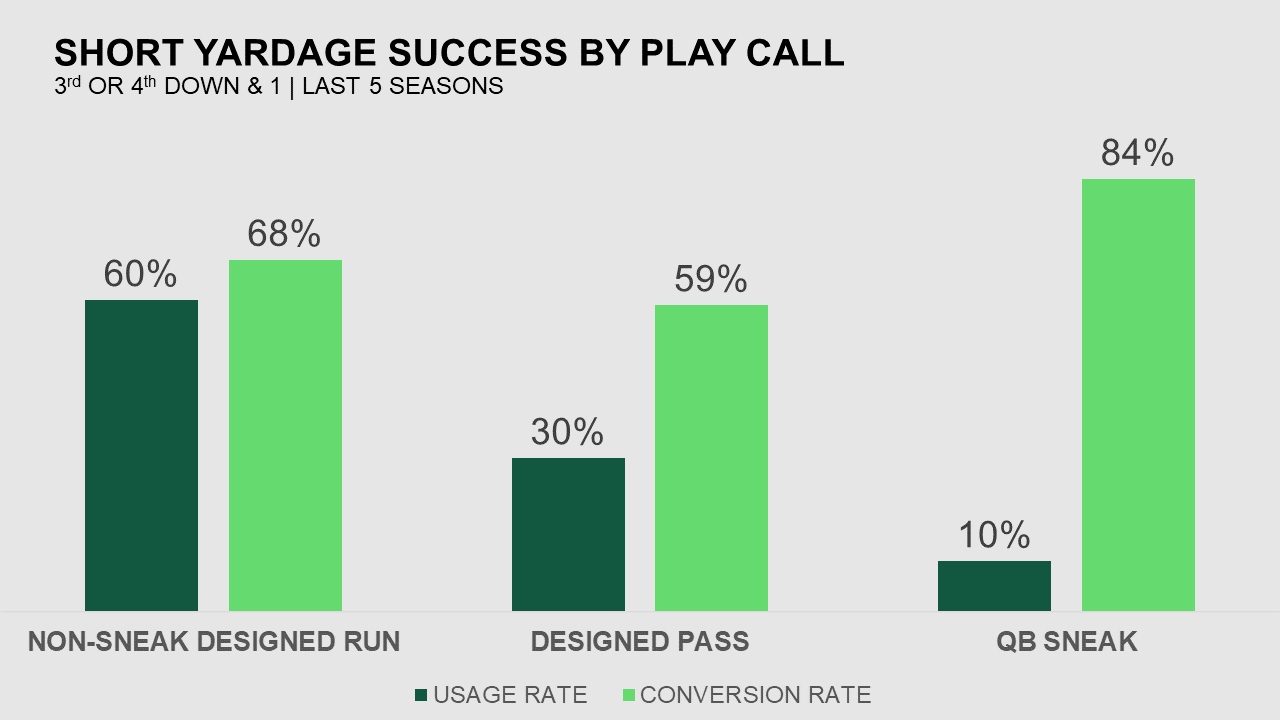

To see how this plays out in practice, consider NFL play-calling. Winning in the NFL is hard, but you can improve your odds by keeping the opposing offense off the field. When faced with converting a short-yardage situation where success means keeping possession of the ball, having the quarterback (QB) run behind the offensive line has resulted in a first down 84% of the time over the last five years. There are few guarantees in life, but with those odds, it’s about as close as you’ll come in a game of skill.

And yet, coaches have only used that formation 10% of the time.

What’s happening here? Nine times out of ten, NFL coaches call a play with a significantly lower success rate than the QB sneak. One could argue that the play is so effective because it’s used infrequently, but it’s hard to imagine a play-calling strategy with a higher mix of QB sneaks wouldn’t result in a net increase in first downs.

In these high-pressure moments, it’s doubtful that the coach doesn’t want to win. Here, loss aversion is likely still in play, but it’s not the game they’re worried about; it’s their job.

The quarterback is arguably the most valuable player on the field, and putting them in harm’s way is a good way to get put on the hot seat. The sneak is significantly safer than a dropback pass where the quarterback is exposed to open-field or blindside hits where injury risks are significantly higher. However, it’s not statistics that stand out in our minds; it’s frequency. If your quarterback gets hurt on a common play, the masses will consider it an unfortunate event but a risk of the game. But if someone gets hurt on a play rarely seen, it’s easier to blame the play call than probability.

In other words, conventional failure preserves your career. Unconventional failure ends it.

Running with the herd is easier than leading the pack when your livelihood is on the line.

Perhaps the most unsettling truth about safety is this: it’s appealing not because it prevents failure but because it spares us from having to explain our failures.

A failed consensus choice comes with a built-in alibi - everyone else would have done the same thing. But a failed unconventional choice? That requires justification, defense, explanation. We optimize for accountability, not outcomes.

This is why great leaders aren't just comfortable being wrong - they're comfortable being wrong in ways that no one else would dare to be wrong. They understand that the path to extraordinary results requires extraordinary mistakes.

The point is this: if your goal is above-average results, you can't get there by chasing safety. Yet that's exactly what we do - through increasingly sophisticated forms of avoidance that we mistake for strategy.

The Three Illusions: How Safety Undermines Excellence

These patterns are subtle but devastating. They feel like prudent management but systematically destroy the possibility of excellence:

The Illusion of Balance - We spread resources evenly across priorities, calling it "comprehensive" or "strategic," which is an implicit preference for activity over outcomes. We guarantee we'll be great at nothing when we try to be good at everything. Real impact requires the courage to choose what matters most. Excellence demands concentration.

The Illusion of Certainty - We gather more data, build more models, seek more validation. But excellence lives at the edge of uncertainty, where data runs out and judgment begins. Analysis should inform our leaps forward, not justify our standstill. Every datapoint that delays action is a shield against excellence.

The Illusion of Discovery- We launch initiatives under the banner of "learning and discovery," stating unequivocally “we’re going to learn” but without any specific hypothesis to prove wrong. This isn't science; it's structured wandering. We can always claim success because we never committed to what success looks like. Excellence requires the courage to be precisely wrong, not vaguely right.

The Right Risks

Excellence isn't about eliminating risk but choosing the right ones. Start by identifying one "safe" choice in your organization that's holding you back. Perhaps it's a legacy system everyone curses but no one replaces, a meeting everyone attends but no one values, or a process that protects reputations but destroys results.

Then ask yourself: What would excellence look like here? Not adequacy, not industry standard - excellence. Between your vision and current reality lies the cost of caution.

Playing it safe isn't playing to win. It's just a respectable way to lose.