Lean & Large

Leveraging natural cycles to grow a business efficiently

When asked about his remarkable physical transformation for It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Rob McElhenney offered a simple explanation:

Look, it's not that hard. All you need to do is lift weights six days a week, stop drinking alcohol, don't eat anything after 7pm, don't eat any carbs or sugar at all, in fact just don't eat anything you like, get the personal trainer from Magic Mike, sleep nine hours a night, run three miles a day, and have a studio pay for the whole thing over a six to seven month span. I don't know why everyone's not doing this. It's a super realistic lifestyle and an appropriate body image to compare oneself to.

Rob McElhenney's sardonic description reveals an uncomfortable truth about efficient growth: it's neither efficient nor sustainable. His "perfect" transformation required unsustainable precision, resource abundance, and single-minded focus.

Sound familiar? It should. This is exactly how we talk about corporate growth in 2025. Just optimize everything. Eliminate all waste. Grow efficiently. All as if perfect execution alone could guarantee sustainable growth.

But McElhenney's transformation worked precisely because it was unsustainable - a focused sprint of growth that required extraordinary resources (studio backing), extreme discipline (strict regimen), and singular focus (no competing priorities).

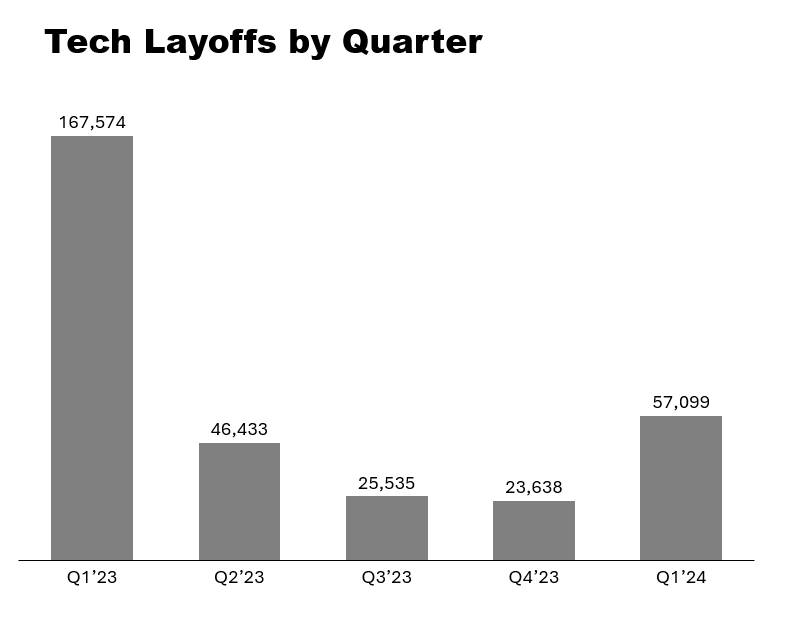

The tech industry's current upheaval shows what happens when we chase this impossible standard of sustainable efficiency. During the zero interest rate period (ZIRP), companies had abundant capital but lacked discipline. Now they're swinging to the opposite extreme - cutting 260,000 jobs in 2023 alone in pursuit of perfect efficiency. Both approaches miss a fundamental truth: growth isn't always meant to be efficient.

While the broader economy has remained stable, tech companies are wrestling with a fundamental reset in how they think about growth. The conventional wisdom points to two factors:

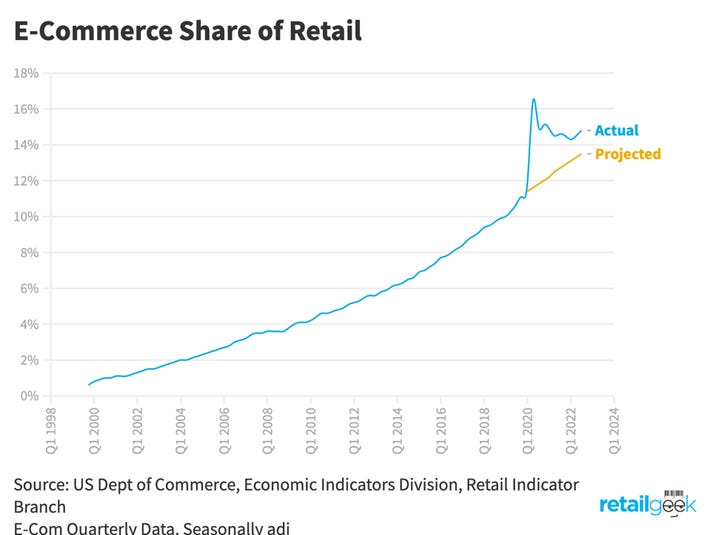

Companies overbuilt during COVID, misreading temporary demand spikes as permanent shifts

Capital now has a real cost, forcing harder choices about which projects to pursue

But this explanation misses something deeper. The real story isn't about mistakes but the fundamental nature of growth itself.

Any organism or organization facing rapid change has three options:

Get Large - Build aggressively to capture the opportunity, accepting that growth will be messy

Get Lean - Preserve resources and efficiency, risking missed opportunities

Maintain - Wait for more clarity, knowing the choice will eventually be forced

During COVID, tech companies that chose to "Get Large" weren't ignoring efficiency - they were acknowledging that explosive growth is inherently inefficient. Those who tried to "Get Lean" preserved their resources but watched competitors capture market share they'll never recover.

This tension creates a natural cycle: periods of aggressive, inefficient growth followed by necessary consolidation and refinement. The companies that get in trouble aren't the ones who grow messily - they're the ones who don't recognize when it's time to shift between these phases.

This creates a deeper strategic challenge. As we discussed in The Dangers of Playing It Safe, following the crowd guarantees average results. The real opportunities come from taking non-consensus positions - deliberately choosing a different path than your peers.

But here's the paradox: when growth opportunities appear, everyone faces the same pressures to "Get Large." Choosing to "Get Lean" requires the courage to look wrong while others grow. Choosing to grow requires accepting inefficiency while others optimize.

So the question isn't whether to grow efficiently - it's how to navigate these cycles with intention rather than being pushed around by them.

The companies that chose to "Get Large" during COVID weren't necessarily wrong. The e-commerce shift was real - they just overestimated its magnitude. But here's the key insight: their real mistake wasn't growing too fast, but failing to recognize when it was time to shift gears.

This points to a crucial truth about growth: the problem isn't that growth is inefficient - it's that we keep trying to make it efficient.

When you try to grow "efficiently," you end up neither truly growing nor truly efficient. It's like trying to gain muscle while staying lean - the physics don't (naturally) work that way. You either starve the muscles you’re trying to build, or you’re so focused on growth that you don’t notice most of what you’ve gained is fat.

This brings us to the core insight: when you commit to getting large, you will inevitably get too large. It's not a mistake - it's physics. Growth requires experimenting with new approaches, entering new markets, trying new strategies. Some of these bets will work perfectly. Many won't. But these "inefficiencies" aren't failures - they're the necessary cost of learning what works.

Getting more than you bargained for in times of growth isn't a function of greed or poor judgment - it's just how growth works. In nature, in bodybuilding, and yes, in business.

This points to a crucial distinction that most companies miss: the difference between trying to grow efficiently and managing growth efficiently.

Growing efficiently means attempting to eliminate waste during periods of expansion - a recipe for stunting your growth. Managing growth efficiently means embracing the natural cycle between periods of aggressive growth and strategic consolidation.

The key isn't to avoid inefficiency - it's to get better at shifting between these phases with intention.

The Natural Rhythm of Growth

At its core, growth follows a simple formula: combine stimulus with supply. A muscle grows when stressed and fed. A business grows when opportunity meets resources.

But here's where most growth strategies go wrong: they try to optimize this formula for efficiency, as if the right balance of inputs could eliminate waste. This fundamentally misunderstands how growth works.

Consider competitive bodybuilding - perhaps the most scientific approach to intentional growth we have. Yes, it's technically possible to build muscle while staying lean, just as McElhenney showed. But it requires unsustainable levels of precision, resource abundance, and single-minded focus. Most athletes, like most companies, can't maintain that perfect balance indefinitely.

Instead, most successful bodybuilders embrace a different approach: deliberate cycles of growth and refinement. During bulking phases, they accept some fat gain as the cost of building muscle. During cutting phases, they accept some muscle loss as the price of getting lean. The art isn't in avoiding these trade-offs, but in managing them strategically.

This cycling approach works because it acknowledges two fundamental barriers to sustained efficient growth:

Aversion to bloat. Nature abhors a vacuum, and humans abhor waste. In any growth endeavor, we’re hyperaware of external signals that we are (or could be) failing. If we fail to realize some level of waste is expected, we could starve the growth in our efforts to eliminate the excess. In our muscle building example, we tend to undermine our gains because we fear adding fat to pursue muscle. This fear of fat causes us to undereat, creating a caloric deficit, which means our body can't adequately feed the growth we're working towards.

Capacity for precision. We tend to confuse the abundance of data available to us with the precision in which we can wield it. Data is naturally messy, and our over-reliance on what numbers say compounded by our inability to consider alternative interpretations of the output tends to result in surprises. For example, our muscle growth model presupposes you know (1) how many calories you burn and (2) how many calories you consume. Unfortunately, standard tools such as fitness trackers and food labels are notoriously imprecise, with error rates of up to 90 percent and 20 percent per FDA guidelines, respectively.

Most competitive bodybuilders have turned these limitations into advantages. Instead of fighting the inefficiencies inherent in growth, they plan for them. Their approach is elegantly simple:

During bulking cycles, they:

Target steady weight gain (0.5-1 pound per week)

Accept that this includes both muscle and fat

Adjust course based on real results, not theoretical targets

Focus purely on growth, knowing they can refine later

During cutting cycles, they:

Switch completely to fat loss mode

Accept some muscle loss as inevitable

Use the same measured approach to minimize losses

Time these phases around competition schedules

The key insight isn't just that they cycle - they fully commit to each phase rather than trying to optimize for everything at once.

The Growth Cycle in Practice

This pattern of intentional expansion followed by strategic refinement isn't unique to bodybuilding - it's fundamental to how growth works in any domain:

Innovation: Consider Nvidia's dominance in AI. They didn't achieve it through careful efficiency - they overbuilt GPU capacity for crypto, accepting massive waste. When that market collapsed, they had the scale ready for the AI boom. Their "inefficiency" became their advantage.

Marketing: As Rory Sutherland notes, effectiveness often requires inefficiency. Wedding invitations sent by mail are "wasteful" compared to email, but that very inefficiency makes them effective. The goal isn't to minimize cost but to maximize impact.

Careers: Molly Graham's J-Curves vs. Stairs framework shows how the most successful careers alternate between risky growth spurts (the J-Curve) and periods of consolidation (the Stairs). Like bodybuilders cycling between bulking and cutting, professionals need both phases to achieve sustained growth.

Making Growth Cycles Work in Practice

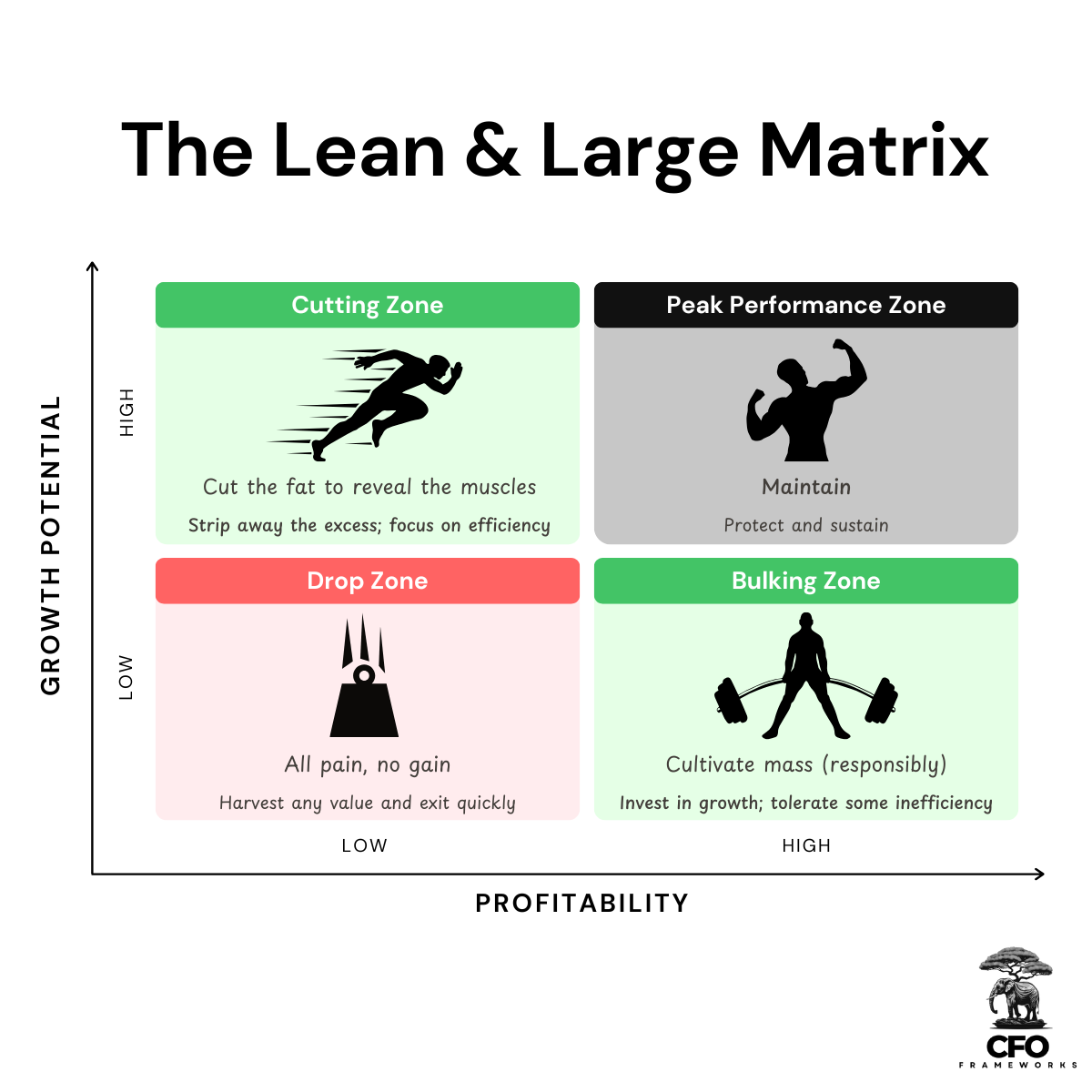

Mastering these growth cycles means first accepting a counterintuitive truth: not every part of your business should be efficient at the same time. Just as bodybuilders can't simultaneously maximize muscle growth and minimize fat across their entire body, companies can't optimize every division at once.

This creates a fundamental challenge: how do you know which parts of your business should be lean and which should be large? The answer lies in understanding where each division sits in terms of its growth potential and current profitability:

Managing across these quadrants requires three key capabilities:

Portfolio Balance

Maintain a mix of bulking and cutting initiatives

Fund growth experiments with optimization gains

Be willing to drop what isn't working to fuel what is

Accept that peak performance is temporary

Measurement Systems

Track both efficiency metrics (unit economics, margins) and growth metrics (market share, ARR growth) across all areas

In bulking zones, allow some efficiency trade-offs to enable growth but maintain minimum performance thresholds

In cutting zones, pursue efficiency gains that don't fundamentally compromise growth potential

Watch for signals that it's time to shift phases

Resource Flexibility

Create distinct but flexible pools for growth and optimization initiatives

Build appropriate buffers - larger for growth experiments, tighter for efficiency projects

Keep some resources mobile to support phase transitions

Maintain optionality without sacrificing commitment to current priorities

The art isn't in perfecting any one phase - it's in managing the transitions between them. Like a bodybuilder cycling between bulking and cutting, success comes from knowing when to shift gears and having the courage to commit fully to each phase.

Conclusion: The Courage to Grow

Don't fret, baby, we're simply growing.

- 8105, Moving Mountains

What we're seeing in today's tech industry isn't a failure of growth strategy - it's a natural part of the growth cycle. The challenge isn't that companies grew inefficiently during ZIRP, or that they're cutting too aggressively now. The challenge is that we keep trying to eliminate these cycles rather than master them.

The path forward requires three shifts in how we think about growth:

Accept the Physics - Growth will always generate some waste. The goal isn't to eliminate inefficiency but to make it productive.

Embrace the Rhythm - Like bodybuilders alternating between bulking and cutting, companies need to intentionally shift between expansion and optimization.

Focus on Timing - The key skill isn't growing efficiently - it's recognizing when to shift between phases. Get this right, and the inefficiencies become investments in your next phase of growth.

The companies that will thrive aren't those pursuing perfect efficiency. They're the ones learning to dance between these phases with intention, understanding that sustainable growth isn't about avoiding waste - it's about turning today's inefficiencies into tomorrow's advantages.