Decision Debt: The Hidden Cost of Every (In)Action

How today's shortcuts become tomorrow's constraints — unless you intervene

Every action you take — and every decision you defer — creates leverage. It either multiplies your opportunities or magnifies your risks. The latter accumulates over time, creating significant drag as “what is” limits “what could be.” Just ask the American railway companies of the 1830s.

England and America built their first modern railways within a year of each other: the Liverpool and Manchester Railway (1830) and the Mohawk & Hudson Railway (1831). Each set the space between the rails (i.e., the rail gauge) at 4 feet 8 1⁄2 inches.

As railroads proliferated throughout the 1830s and 1840s, so too did the variety of gauge sizes. Few based their selection solely on engineering criteria. In some cases, it was a matter of familiarity, aligning the gauge with the width of the transportation lanes the railway was replacing. In others, it was a strategic decision, fending off competitors or neighboring nations from connecting to their rails.

This made things complicated. By the 1870s, America utilized over twenty different gauges varying anywhere from five to seven feet. Left to their own devices, the railways had created a transportation network that would force passengers and cargo to switch trains at each junction. Something had to be done.

The Americans tried everything except addressing the root cause. They built adjustable wheels, modified tracks, and even used cranes to lift entire train cars between different gauges. Each solution worked just well enough to avoid facing the real problem: the lack of standardization.

So many innovations, so little progress. After years of working around the problem, the writing was on the wall. As long as the railways were allowed to set their own gauges, long-distance train travel was neither safe nor efficient. Gauge standardization was the only solution.

During the Transcontinental Railroad development in 1869, railways were torn up and replaced with the standard 4 feet 8 1⁄2 inches gauge first installed over 30 years ago. The change was expensive but not nearly as disruptive as expected. Standardization enabled an unparalleled focus on a singular solution. Focus brought efficiencies, as exemplified by Louisville and Nashville’s replacement of a combined ~2,000 miles of track within one day.

As impressive as this was, it wasn’t revolutionary. The British came to the same conclusion more than 20 years earlier. As the Americans toiled with solutions to a problem they created, the British solved the problem at its source by enacting the Railway Regulation Act, which defined the same 4 feet 8 1⁄2 inches gauge as standard, banning all others.

The American approach is a stark reminder of how our past decisions can shape our trajectories. Each decision creates a commitment that reduces our option pool. Each commitment acts as a form of leverage; it can amplify our outcomes either positively or negatively.

Much like debt.

Decisions as Debt

The parallels between financial and decision debt are striking:

Like a mortgage, some decisions fund transformative growth

Like credit card debt, others trap us in cycles of inefficiency

Like leverage ratios, there's a tipping point where flexibility becomes fragility

Like compound interest, the cost of deferring hard choices grows exponentially

The key is knowing which decisions are investments and which are indulgences.

Starting a company. Going to graduate school. Buying a home. These potentially life-changing events would be largely unattainable if they were only available to those who had the cash in hand. It is when the cost outweighs the benefits of our outstanding commitments that we get into trouble.

In finance, this is known as debt overhang. Think of it as a borrowing black hole, where the debt burden looms so large that it consumes all available resources. Even if a golden opportunity presents itself, there’s no way to pursue it, as every incremental resource generated is needed to fund the obligation. The commitment becomes a condemnation. Debt becomes a four-letter word.

Our decisions work in much the same way. Just as the American railways' initial gauge choices seemed rational but created mounting infrastructure debt, organizations today face similar crossroads.

Every commitment creates constraints - the question is whether those constraints will focus or fragment our efforts.

Take technology standardization. Like Britain's early gauge regulation, a well-planned standard can create powerful efficiencies. Microsoft's decision to standardize Windows development on .NET in 2002 enabled rapid innovation. But contrast this with IBM's commitment to mainframes in the 1980s - what began as a strength became a constraint that nearly crippled the company during the PC revolution.

The key is distinguishing between constraints that create leverage and those that create liability. Amazon's "two-pizza team" rule deliberately constrains team size to enhance productivity, much like how standardized rail gauges enabled faster and more efficient transportation. Yahoo's pre-2013 office-only policy, on the other hand, mirrors the fragmentation of American railways: a constraint that seemed logical but ultimately limited growth and innovation.

This bifurcation process is easier said than done. All decisions should be viewed in context, meaning one shouldn’t shy away from reversing course on what was a good decision in the past.

Consider 1Password, which didn’t take outside funding until (too) late in the game:

Brett: Do you look back and you can clearly see that at certain points there would have been benefits if you chose to raise capital?

Jeff: Hindsight being 20/20, I would've raised capital earlier. You can get to a point where you're proud of things you should no longer be proud of. Maybe said a better way the things that you're proud of can inhibit you…once you've been bootstrapped for 10 years and everybody's like, wow, you've grown this, great company, all bootstrapped, how impressive is that, that becomes becomes your identity.

…If we had had marketing and go-to market and like real marketing, if we had been more mature earlier, that would've helped us…

The choice to be bootstrapped became a badge of honor, and the badge of honor became a constraint. The team had to overcome the (perceived) negative of taking on outside capital to accelerate their growth, because they recognized that growth would be inefficient in the short term.

Decisions are force multipliers because they focus our resources. Just like debt consumes a percentage of future earnings, decision debt consumes future opportunities that otherwise would’ve been available to us if we’re not careful.

If we make the right choices, the payoff is massive. If not, we fall behind to the point where we may never catch up.

The Hidden Patterns Behind Decision Debt

Decision overhang is dangerous because it’s a gradual process. Think of each decision as a swipe of a credit card - a series of individually small purchases can put us into the same bind as a singular, massive one. Keeping our decision debt manageable requires that we:

Reflect on how past decisions affect us today and

Remember what decisions were made.

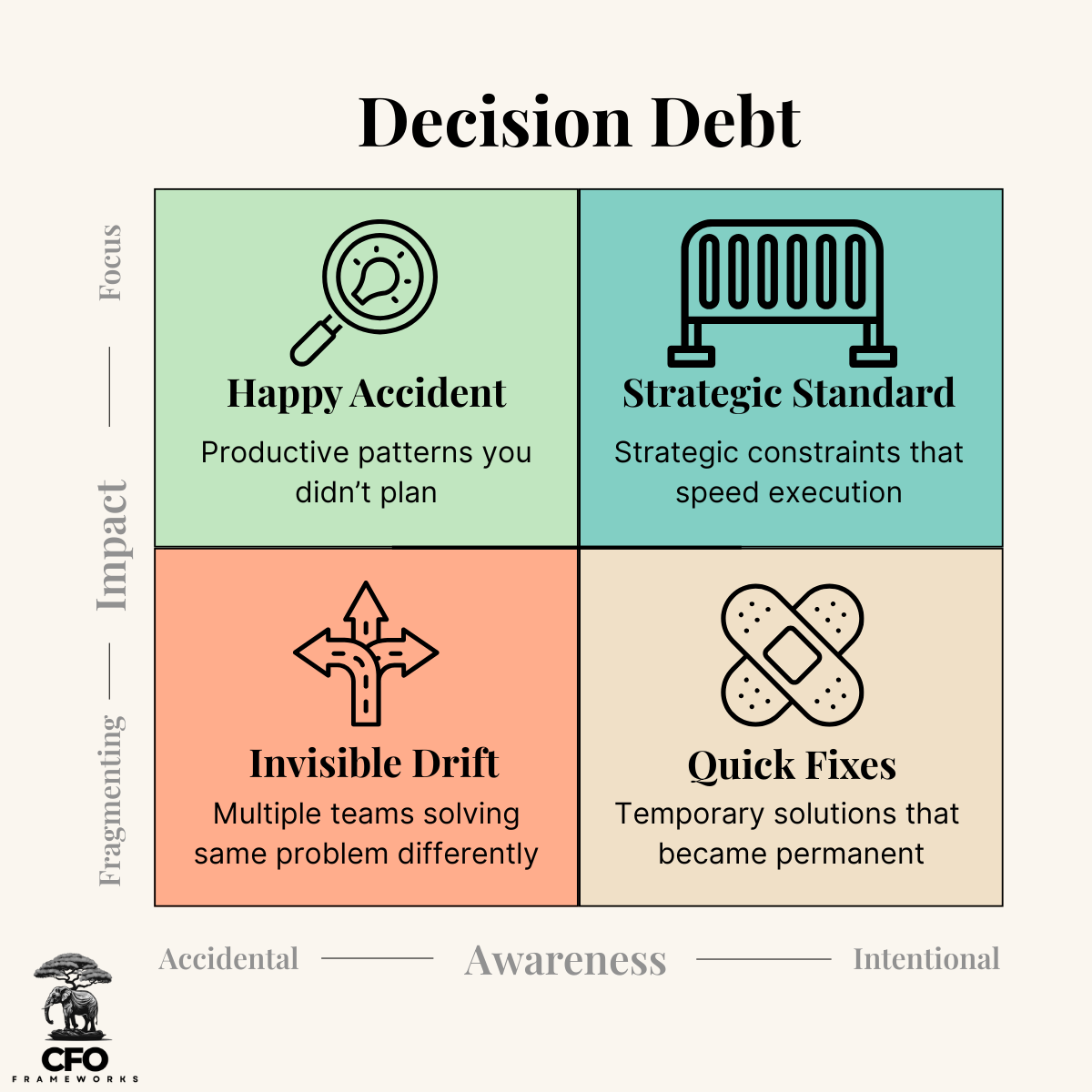

To make this distinction, it helps to think about decisions across two dimensions:

Awareness (Was the decision made deliberately or accidentally?): The American railways didn't intend to create a fragmented network - it emerged from many local decisions. Britain, in contrast, deliberately standardized their gauge early. The difference between intentional choices and unconscious patterns often determines whether we can manage their consequences.

Impact (Does the decision create focus or fragmentation?): Some constraints, like Amazon's two-pizza team rule, channel energy in productive directions. Others, like IBM's mainframe commitment, scatter resources across incompatible efforts. The key is distinguishing between decisions that concentrate power and those that dissipate it.

These dimensions create four distinct patterns:

Invisible Drift (Most Dangerous)

What it looks like: Multiple teams solving the same problem differently

Example: Different business units building their own billing systems.

Response: Stop the bleeding, then standardize

Quick Fixes (Most Common)

What it looks like: Temporary patches that quietly become permanent.

Example: Manual reporting workarounds that never get automated.

Response: Set hard deadlines for cleanup and systemization.

Happy Accidents (Most Overlooked)

What it looks like: Productive patterns you didn't plan

Example: Teams naturally adopt an efficient project rhythm without formal training.

Response: Spot it early. Codify and scale what’s working.

Strategic Standard (Most Valuable)

What it looks like: Clear constraints that speed up alignment and execution.

Example: Britain’s early nationwide railway gauge regulation.

Response: Strengthen the standard. Build momentum around it.

Turning the Tide: How to SCAN for Decision Debt

Warning Signs Your Decision Debt is Becoming Dangerous:

More than 20% of resources maintaining workarounds

Three different solutions to the same problem

Rising coordination costs between teams

Increasing resistance to change

Growing backlog of "temporary" fixes

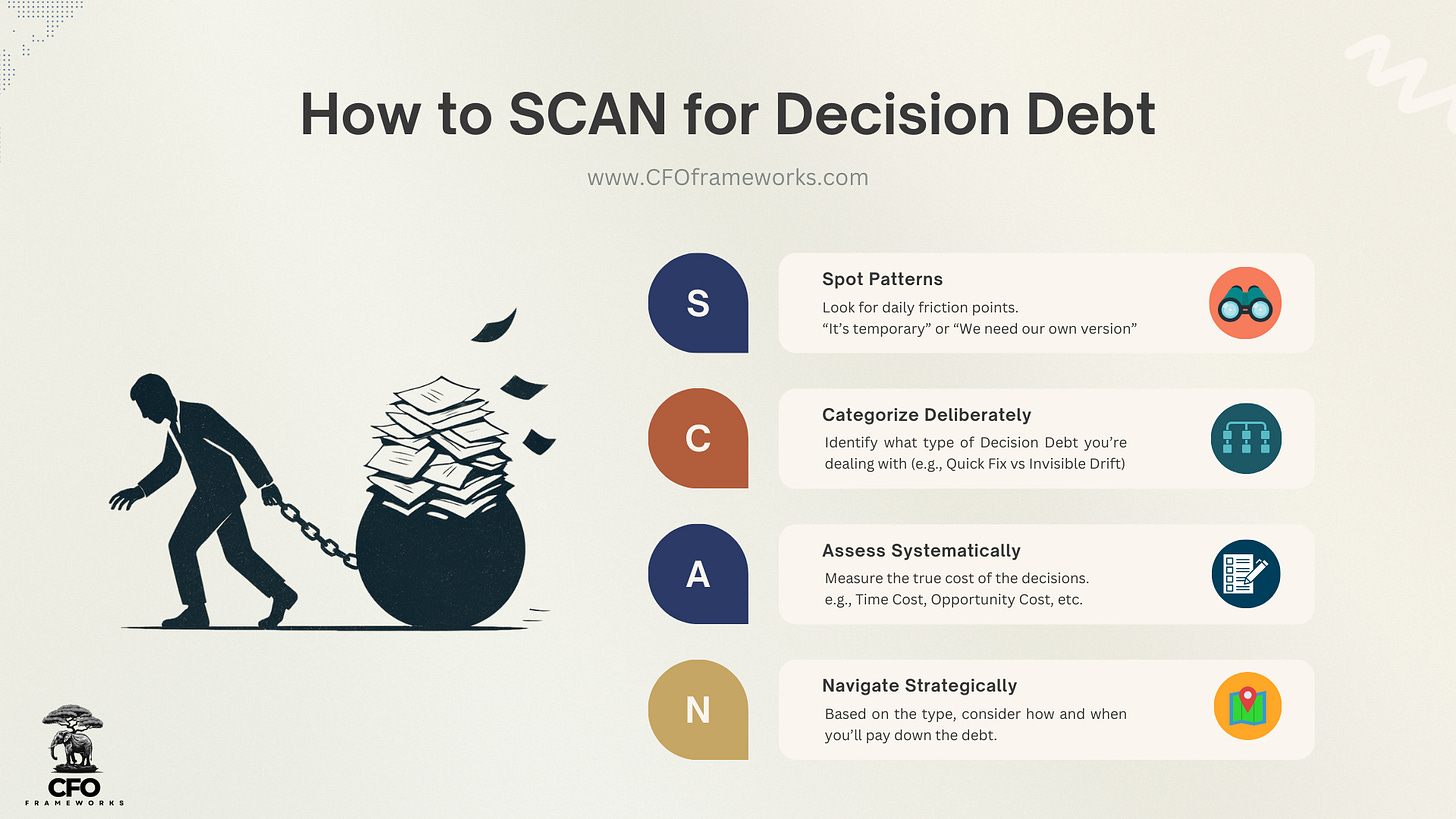

The good news? Like financial debt, decision debt can be restructured. The SCAN framework helps you move from reactive to strategic decision-making.

When we think about our decisions in this way, we can determine which ones continue to serve us and which hold us back. Decision debt is inevitable, but decision overhang is not.

The path forward is clear: we must become active managers of our decision debt. This means developing a systematic way to SCAN our environment:

Spot Patterns

Like the early signs of railway incompatibility, decision debt often reveals itself through daily friction:

Multiple departments building similar tools ("We needed our own version")

Increasing time spent on workarounds ("It's just temporary")

Rising coordination costs between teams

Resistance to standardization ("Our case is different")

Warning Signs:

More than 20% of team time spent on maintenance

Three or more solutions to the same problem

Regular exceptions to standard processes

Growing backlog of "technical debt"

Categorize Deliberately

Ask these questions to identify which pattern you're dealing with:

Quick Fix: "Was this meant to be temporary?"

Invisible Drift: "How many ways do we do this?"

Strategic Standard: "Does this constraint speed us up?"

Happy Accident: "What's working well without formal structure?"

Key Questions for Teams:

"If we started fresh, would we make this choice again?"

"Are we solving symptoms or root causes?"

"What patterns emerged naturally vs. by design?"

Assess Systematically

Measure the real cost of your decision patterns:

Time Cost: Hours spent maintaining multiple solutions

Opportunity Cost: Innovation prevented by maintenance

Coordination Cost: Effort required to keep teams aligned

Future Cost: Growing difficulty of eventual changes

Prioritization Matrix:

High Impact/Low Effort: Address immediately

High Impact/High Effort: Plan strategic resolution

Low Impact/Low Effort: Fix opportunistically

Low Impact/High Effort: Accept or deprecate

Navigate Strategically

Choose your approach based on pattern type:

For Quick Fixes:

Set firm timelines for permanent solutions

Build replacement into regular sprint cycles

Get stakeholder buy-in for short-term pain

Document current state to prevent recurrence

For Invisible Drift:

Map all current approaches

Calculate total maintenance cost

Pilot standardization with willing teams

Create clear migration paths

For Strategic Standards:

Document what makes them effective

Spread adoption through demonstration

Measure and share positive impact

Build supporting infrastructure

For Happy Accidents:

Study why they work well

Formalize best elements

Scale gradually with monitoring

Maintain flexibility in implementation

Getting Started

Choose one area showing warning signs

Map current state using the framework

Pick one high-impact, achievable change

Set clear metrics for success

Review progress monthly

Common Pitfalls:

Trying to fix everything at once

Focusing on symptoms over causes

Neglecting stakeholder buy-in

Forgetting to measure baseline state

The Cost of Waiting

The American railways eventually standardized their gauge, but only after decades of costly workarounds. Their story offers a sobering reminder: the interest on decision debt compounds daily.

Every month you delay addressing systematic problems, you pay a premium in:

Lost opportunities

Wasted resources

Declining morale

Competitive disadvantage

Take Action Now:

Map your current decision debt using the framework above

Choose one high-impact area to address

Set clear metrics for progress

Review and adjust monthly

Share your learnings

The question isn't whether we'll accumulate decision debt - we will. The question is whether we'll manage it systematically or let it manage us.

Ready to share this?

If you found it helpful, forward it to your team or peers. Great finance leaders spread clarity, not chaos.

And, if you haven’t already, please subscribe to never miss a post!