A Light Touch

The useful leadership skill that creates capable, empowered teams

“I just don’t see myself here in a year’s time.”

I was floored. It was my first review cycle with a high-performing manager I’d hired, and there she was telling me that she didn’t care for the job. She loved the people and her business partners, but her scope and responsibilities were much narrower than what she had been promised.

And it was my fault.

In my effort to shield her from the aspects of the job that could make her miserable, I had inadvertently protected her from challenges and, consequently, from any growth.

I thought I was being helpful. I was wrong.

Peter Drucker, the father of modern management, once gave Jim Collins a perspective-shifting challenge. Collins was agonizing over leaving his faculty position at Stanford, worried about survival and success. Drucker cut through his anxiety with a single, penetrating question:

“It seems to me you spend a lot of time worrying how you will survive,” said Peter. “You will probably survive.”

He continued, “And you seem to spend a lot of energy on the question of how to be successful. But that is the wrong question.”

He paused, then like the Zen master thwacking the table with a bamboo stick: “The question is: how to be useful!”

It’s deceptively simple. Being useful sounds straightforward, even mundane. But when we dig deeper, we discover that true usefulness isn’t about what we accomplish—it’s about what we enable in others. And that’s where most of us get it wrong.

The temptation is to equate usefulness with personal achievement.

If I accomplish more, I’ll be useful.

If I stand out, I’ll be useful.

If I make my mark, I’ll be useful.

But real usefulness rarely works that way, especially as you take on greater responsibility. The more senior you become, the less the job is about what you accomplish, and the more it’s about what you enable in others. And that shift—from doing to enabling—is where many of us get it wrong.

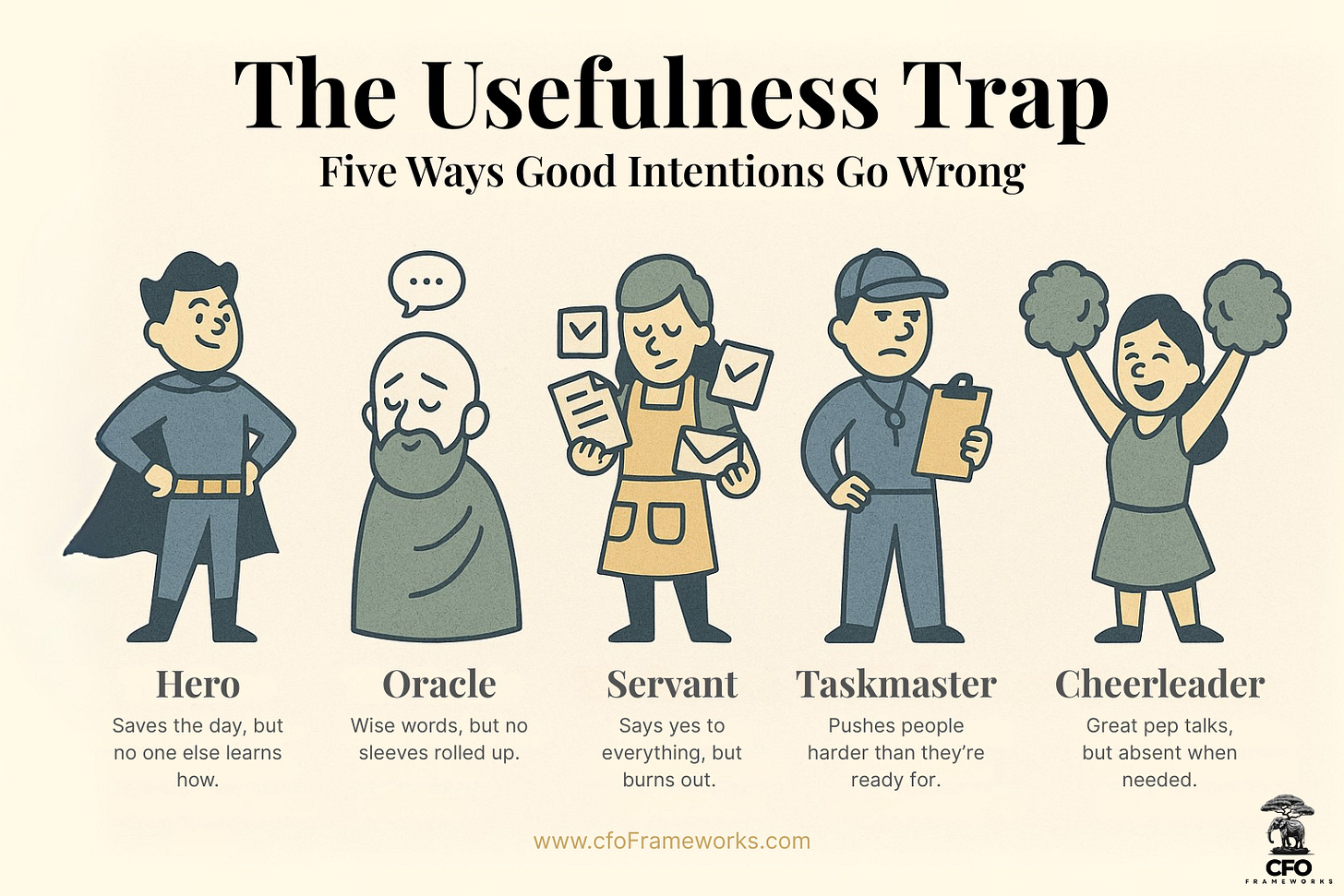

The Usefulness Trap

The challenge of being useful, especially in leadership, is that it feels like it should be simple.

See a problem, solve a problem. Notice a gap, fill a gap. Help where help is needed.

But anyone who's tried to mentor a junior colleague, manage a team, or even help a friend knows that it's rarely that straightforward. I learned this lesson the hard way early in my career, watching a senior leader try to "help" his team by staying late every night to review and polish their models. Six months later, the team's output had decreased - they'd learned to wait for his improvements rather than develop their own skills.

We've all been there, haven't we? Watching someone struggle with a problem we know how to solve, itching to jump in and fix it. Or maybe we're on the other side, grinding our teeth as someone offers well-meaning but unhelpful advice from the sidelines.

It’s easy to get this wrong, even with the best intentions. In fact, most failed attempts at being useful fall into a handful of predictable traps:

The Hero jumps in to solve every problem, working nights and weekends to keep projects on track. They're the first to volunteer and the last to leave. But their relentless helpfulness creates a vacuum - when they're out sick, the whole team grinds to a halt. They've become so essential that they're actually harmful.

The Oracle dispenses wisdom from on high, offering profound insights without ever getting their hands dirty. "Have you considered approaching this from a different angle?" they ask, before floating away to their next meeting. Their advice might be sound, but without practical support, it's just philosophy.

The Servant says yes to every request, maintaining an ever-growing to-do list of other people's priorities. They're everyone's favorite colleague until they burn out, leaving dozens of half-finished projects in their wake.

The Taskmaster believes in tough love, pushing people toward their potential whether they're ready or not. "I'm just trying to help you grow," they explain, as another teammate updates their resume.

The Cheerleader offers endless encouragement but no substantive support. "You've got this!" they declare, while you're drowning in problems they could actually help solve.

Each of these postures can feel useful—even wise—in the moment. But as I’ve written before, confident and completely wrong leadership is one of the easiest traps to fall into.

Each archetype represents a different way of getting the balance wrong - doing too much, too little, or the wrong kind of help entirely.

And here's the cruel irony: the more determined we are to be useful, the more likely we are to fall into these traps. Our very intensity pushes us toward extremes.

We need a more nuanced approach. A light touch.

A Light Touch

What we need isn't more effort or better intentions - we need a completely different approach. Instead of force, we need finesse. We need what I call a "light touch."

Think of teaching someone to ride a bike - it's all about finesse. Push too hard, and they'll speed out of control. Let go too soon, and they'll fall. But find that sweet spot - a gentle hand ready to steady but not control - and they're flying down the street on their own in no time.

That same balance applies in leadership, coaching, and life. And surprisingly, one of the best illustrations I’ve seen doesn’t come from a business book or management guru. It comes from Futurama.

In Godfellas, Bender (the robot) becomes the god of a tiny civilization that develops on his body after colliding with an asteroid as he hurls through space.

The civilization grows and thrives under Bender's care, but he eventually realizes that being a god is not as easy as it seems. In his attempts to heed his worshippers’ prayers, he ultimately wins the affection of some but disillusions others. This bifurcation of the populace horrifies him, and when asked to favor a side between the factions, he refuses.

[Spoiler] Ultimately, the two groups kill each other in an all-out war. [Spoiler]

Bender then encounters a cosmic entity (who may or may not be God), and they discuss the challenges of placating their followers.

Bender: You know, I was God once.

God Entity: I saw. You were doing very well, until everyone died.

Bender: It was awful. I tried helping them. I tried not helping them. But in the end, I couldn’t do them any good.

We can all relate here…well, maybe not with the being a god part, but this struggle between our intentions to help and the ramifications of our intervention is a very human (or robot) issue. In our pursuit of usefulness, we can do more damage than good.

And here, finally, is where we get a semblance of a framework to help us.

God Entity: If you do too much, people get dependent on you. And if you do nothing, they lose hope. You have to use a light touch, like a safecracker or a pickpocket.

Bender: Or a guy who burns down a bar for the insurance money!

God Entity: Yes, if you make it look like an electrical thing. When you do things right, people won't be sure you've done anything at all.

To be clear, I’m not equating usefulness to godliness. Nor am I advocating adopting the mindset of a safecracker, pickpocket, or insurance fraudster.

But this is, at its core, the skill great leaders master: knowing how to help without creating dependence, and when to step back to foster real growth.

The underlying lesson is balance - not too much intervention as to invite dependence, not too little as to breed hopelessness. Usefulness is a sweet spot in which our presence is felt but not focal. When our efforts are appreciated but have no claim on the successful outcome, we’ve done things right.

Go back to the Jim Collins story at the top. Peter’s contribution wasn’t heavy-handed (“You should write best sellers for a living!”) or aloof (“You’ll be happy no matter what you do…now get out of my office.”) Peter used a light touch, challenging Jim’s thinking without telling him how to think.

All of this feels intuitive. Why don’t we do this more often?

What often gets in the way of this model is our ego. Regardless of where we are in our careers or lives, we rarely feel like we have the luxury to shrug off receiving credit. The tangible accomplishments we can put our name to feel better than the accomplishments of others that we influenced. The items in our personal wins column make us feel safe. Who gets credit matters, doesn’t it?

Maybe not. In this model of usefulness, what you accomplished may not be clear, but your influence on the environment will be undeniable.

Think of it this way: Nobody buys a jersey with the coach’s name on the back, but nobody denies the impact of a great coach on the team.

Perhaps it’s easier to see an example. Let’s look at one of the most successful coaches in Silicon Valley history.

The trillion-dollar coach

Bill Campbell may be the most famous person you’ve never heard of.

He was integral to the success of companies like Google, Apple, Amazon, Twitter, and Facebook. His success in coaching these companies’ leaders to build world-class organizations earned him the title of Trillion-Dollar Coach.

Look at a sample of Bill’s leadership principles and see what you notice about his approach.

Your title makes you a manager; your people make you a leader. Accrue respect, don’t demand it.

It’s the people. The well-being and success of her people is the top priority of any manager. Great people flourish in an environment that liberates and amplifies that energy. Managers create this environment through support, respect, and trust.

Best ideas, not consensus. The manager’s job is to run a decision-making process, ensuring all perspectives are heard and considered. If necessary, break ties to make the decision.

Don’t stick it in their ear. Offer stories and help guide people to the best decisions for them. Don’t tell them what to do.

Be the evangelist for courage. Believe in people more than they believe in themselves.

Bill mastered the concept of a light touch. He supported people - pushed them - but never so much that they grew dependent on him. He intuitively shifted between intervening when needed, supporting when it counted, and stepping back when others were ready to lead.

The focus was always on others - he focused on those he coached so they could focus on those they led. You can’t tie a single accomplishment of these businesses to Bill, yet his impact was felt.

Excellent teams at Google had psychological safety (people knew that if they took risks, their manager would have their back). The teams had clear goals, each role was meaningful, and members were reliable and confident that the team’s mission would make a difference…[Bill] went to extraordinary lengths to build safety, clarity, meaning, dependability, and impact into each team he coached.

When you do things right, you tap into the innate potential of those around you and elevate them to a level never thought possible. Standing back and looking at the whole picture, it will be impossible to decipher how much of the impact was from your coaching versus their execution. And that’s what you want because it doesn’t matter who gets the credit.

When you worry less about who gets credit, the opportunity for impact is limited by how many people you can be useful to.

That’s the posture of the light touch: helping in a way that fosters growth, not dependence. But putting this into practice requires more than good intentions—it takes constant calibration. We need to be deliberate about how and when we offer help.

It’s not about you; it’s about others. And you cannot give yourself to them until you get over yourself!

John C. Maxwell

How to be useful

So how do we know when to lean in - and when to let go?

A light touch doesn’t mean doing nothing. And it certainly doesn’t mean taking control. It means calibrating your involvement to meet the moment, providing just enough support to help others succeed without making them dependent on you.

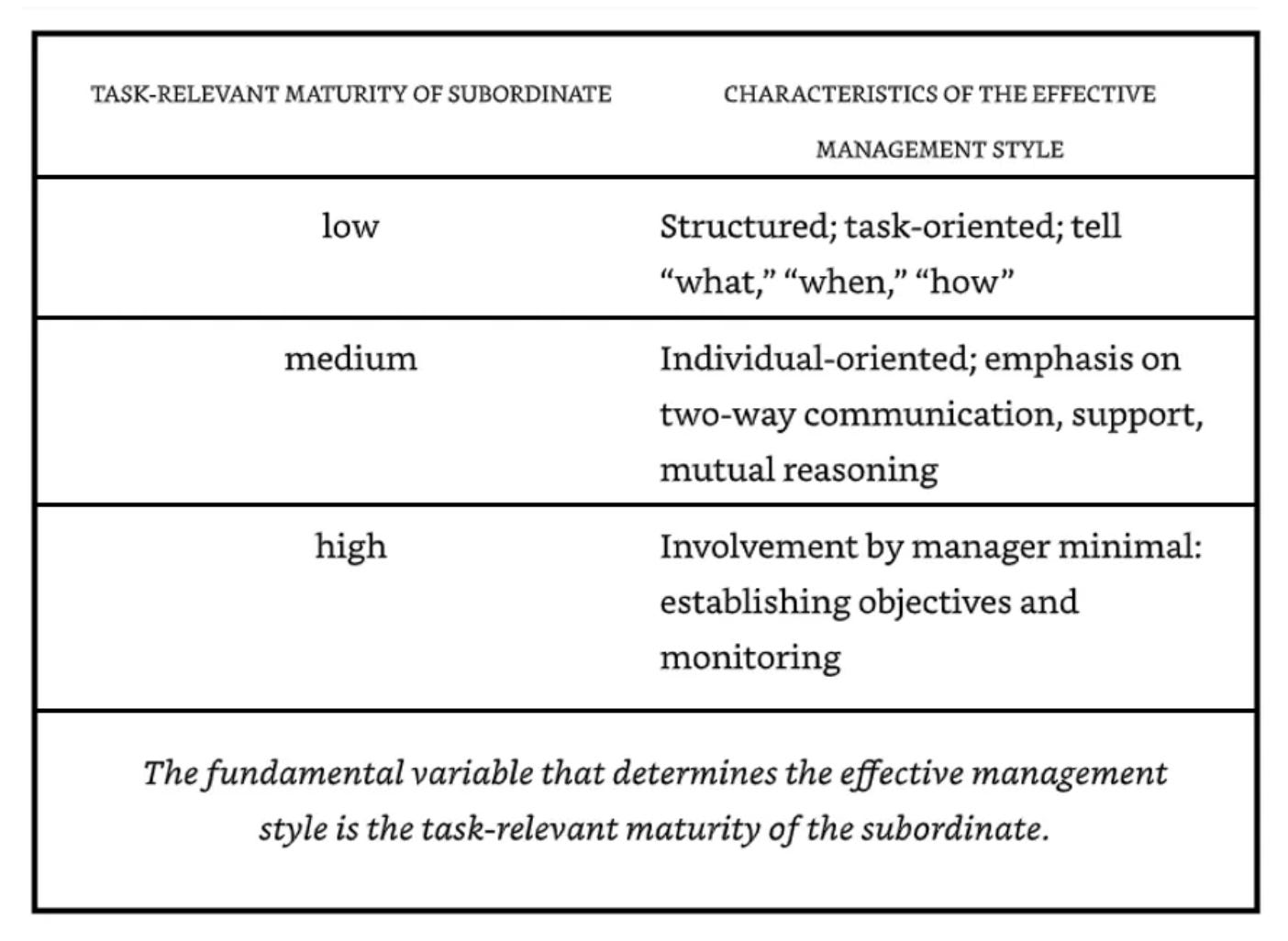

One of the clearest ways I’ve found to think about this comes from Andy Grove, former CEO of Intel. Grove described leadership posture as a function of “Task-Relevant Maturity.”

The idea is simple: how you manage someone should depend on how capable and confident they are in a given area, not how senior or skilled they are.

When task-relevant maturity (TRM) is low—someone is new to a task or domain—you need to be more hands-on. As TRM builds, you shift to supporting: offering guidance without taking control. And when TRM is high, the best thing you can do is step away and give ownership.

The art of the light touch is mastering that shift. Not doing too much or too little—but adjusting how you help, so others grow stronger and more capable over time.

Here are a few ways to apply this in your own leadership - shifting your posture as others grow in task-relevant maturity:

Focus on what you enable, not what you accomplish.

When TRM is low, it’s tempting to jump in and drive outcomes yourself. But from the start, focus on building capability. Shared accomplishments have more impact than solo heroics. Those who put the team on the right path are remembered, while those who cling to defensible control often stall.Be clear on what, flexible on how.

As TRM builds, resist the urge to dictate process. Define what success looks like, but leave space for the team to figure out how to get there. This less beats more approach fosters ownership and intrinsic motivation - the real drivers of growth.Shift your posture over time.

Your primary job is to help people become more effective so that they no longer need your intervention. Pay attention to where each person is on the TRM curve, and adjust accordingly. Intervene when necessary—support when helpful. Step away when ready. That’s the light touch.

Mastering the shift is the essence of a light touch. It’s what separates leaders who create capable, empowered teams from those who unknowingly foster dependence or disengagement.

Even small gestures can have an outsized impact. The real art lies in knowing when to intervene, when to support, and when to step away—adjusting your posture as others grow in capability.

Master that shift, and you won’t just be successful. You’ll be useful.

Next Steps

Take a moment to evaluate your current leadership approach:

How many decisions did you make last week that others could have made?

When was the last time you let someone struggle through a problem you could have solved?

What percentage of your team's success required your direct intervention?

The answers will tell you if you're developing capability or dependency.

Next Steps:

Choose one project where you're currently heavily involved

Identify one aspect you can step back from this week

Document what happens when you do

Remember: The goal isn't to do less - it's to enable more.

When you master the light touch, you create leaders, not followers. You build capability, not dependency. And most importantly, you become truly useful, not just busy.

The question isn't whether you can help. It's whether you can help in a way that makes your help increasingly unnecessary.

Ready to share this?

If this resonated, I’d love it if you shared it. I hope more leaders learn to lead with a light touch—and leave stronger teams behind them.

And, if you haven’t already, please subscribe to never miss a post!

And, finally, check out my interview with Glenn on the FP&A Today Podcast here: